Understanding Juvenile Sexual Offending Behavior:Emerging Research, Treatment Approaches and Management PracticesDecember 1999 IntroductionJuveniles commit a significant number of the sexual assaults against children and women in this country. The onset of sexual offending behavior in these youth can be linked to numerous factors reflected in their experiences, exposure, and/or developmental deficits. Emerging research suggests that, as in the case of adult sex offenders, a meaningful distinction can be made between youth who target peers or adults and those who offend against children. However, juveniles who sexually offend are distinct from their adult counterparts. Youth who commit sexual offenses are not necessarily "little adults;" many will not continue to offend sexually. This is a formative area of research; while there is an ever-increasing body of knowledge regarding the etiologies of dysfunction and aggression, there remains a tremendous need for additional data to understand the etiology of juveniles sexual offending. The purpose of this brief is to discuss the current state of research on sexually abusive youth, legislative trends, and promising approaches to the treatment and supervision of these youth. Research DevelopmentsCharacteristics of Juvenile Sexual AbuseSexual aggression perpetrated by young people has been a growing concern in the United States over the past decade. Currently, it is estimated that juveniles account for up to one-fifth of all rapes and almost one-half of all cases of child molestation committed each year (Barbaree et al, 1993, Becker et al, 1993, Sickmund et al, 1997). Adolescents age 13 to 17 account for the vast majority of cases of rape and child molestation perpetrated by minors (Davis and Leitenberg,1987). The majority of incidents of juvenile sexual aggression involve male perpetrators (Sickmund et al, 1997). However, a number of clinical studies also point to prepubescent youths and females engaging in sexually abusive behaviors. Although racial and socioeconomic differences may be over represented in certain settings (e.g., juvenile justice), juveniles referred for treatment in a variety of environments reflect the same racial, religious, and socioeconomic distribution as the general population of the United States (Ryan et al, 1996).

A number of etiological factors (risk factors) have been identified to help explain the developmental origin of sexual offending. Factors receiving the most attention are abusive experiences and exposure to aggressive role models. Other factors in focus are substance abuse and exposure to pornography; however, these are seen more as disinhibitors than as causal influences. The Effects of Physical and Sexual AbuseRecent studies show that rates of abusive histories vary widely for sexually abusive youth. A history of physical abuse has been found in 20 to 50 percent of these youth; a history of sexual abuse has been found in 40 to 80 percent of sexually abusive youth (Hunter and Becker, 1998, Kahn and Chambers, 1991). Rates of physical abuse and sexual victimization are even higher in samples of prepubescent and young female sexual abusers (Gray et al,1997, Mathews et al, 1997). Research suggests that age of onset, number of incidents of abuse, the period of time elapsing between the abuse and its first report, as well as perceptions of familial responses to awareness of the abuse are all relevant in understanding why some sexually abused youths go on to commit sexual assaults while others do not (Hunter and Figueredo, in press). The influence of abusive experiences is considered multi-faceted and includes effects related to both Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and modeling (Freeman-Longo, 1986, Gil and Johnson, 1992). Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder have been observed in a number of youths with sexual behavior disorders, especially children ages 13 and younger and females. These symptoms include recurrent and intrusive recollections of past traumatic events and increased levels of irritability and anger. Youths who have directly experienced or witnessed sexual abuse may imitate the behavior of the aggressive role model(s) in their interactions with others. The presence of child maltreatment—whether neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, or other forms of victimization—may eventually prove to be a significant predictor of sexual offending behavior. Exposure to Aggressive Role ModelsStudies show that male child witnesses to domestic violence tend to engage in externalizing behaviors (the acting-out of psychological conflict or tension), including acts of interpersonal aggression, more than their female counterparts (Stagg et al, 1989). Exposure to family violence is linked to the likelihood of sexually offending as an adolescent, as well as the severity of psychosexual disturbance (Fagan and Wexler, 1988, Smith 1988). The effects of exposure may be cumulative, as well as interactive with other developmental experiences, such as child abuse and neglect (O’Keefe, 1994). Recent studies suggest that exposure to severe community violence (e.g., murders) may also increase the likelihood of engaging in violent and antisocial behavior (Johnson-Reid, 1998). Substance Abuse and Exposure to PornographyWhile there is strong research to support the association between violent crime and alcohol use, the association between sexual offending and substance abuse is not fully established. Estimates of the extent of substance abuse vary widely for the population of youth who sexually offend (Lightfoot and Barbaree, 1993). The influence of pornography on the developing male’s potential for sexual offending is an issue of similar controversy. One recent study found that sexually abusive youth were exposed to pornographic material at younger ages on the average, and to "harder core" pornography, than either status offenders or violent non-sex offending youths (Ford and Linney, 1995). Research in these areas is lacking and clearly, juvenile sexual offending is far more complex than simple exposure to pornography or substance abuse. Developmental ProgressionWhile sexual aggression may emerge early in the developmental process, there is no evidence to suggest that the majority of sexually abusive youth become adult sex offenders. Recidivism rates for these youth may have been exaggerated by a reliance on retrospective research studies (studies that examine historical data), which can overstate the strength of correlations. Longitudinal studies (studies that examine current data), which tend to be more reliable, suggest that aggressive behavior in youths often does not continue into adulthood, although some portion of those who commit rape may continue to abuse (Elliott, 1994, Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1998). Other Characteristics Common to Sexually Abusive YouthSexually abusive youth share other common characteristics, including:

The following table outlines some of the common characteristics found in youth who sexually offend:

The clinical and criminal dimensions of juvenile male sexual abusers often vary. As with their adult counterparts, juvenile sexual abusers fall primarily into two major types: those who target children and those who offend against peers or adults. The distinction between these two groups is based on the age difference between the victim and the perpetrator (child perpetrators are those who target children five or more years younger than themselves). The following table examines distinctions in characteristics between these two groups of sexually abusive youth.

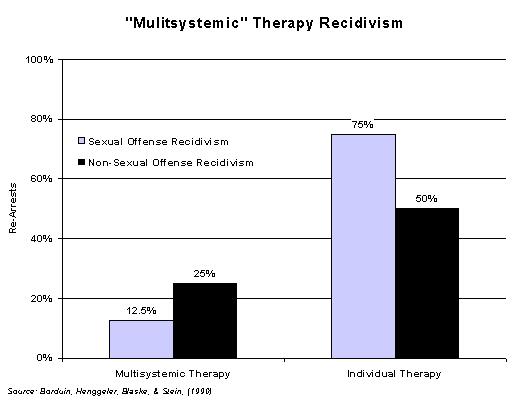

Deviant Sexual InterestsA minority of sexually abusive youth manifest established paraphilic (deviant) sexual arousal and interest patterns. These arousal and interest patterns are recurrent and intense, and relate directly to the nature of the sexual behavior problem (e.g., sexual arousal to young children). Deviant sexual arousal is more clearly established as a motivator of adult sexual offending, particularly as it relates to pedophilia. A small subset of juveniles who sexually offend against children may represent cases of early onset pedophilia. Research has demonstrated that the highest levels of deviant sexual arousal are found in juveniles who exclusively target young male children, specifically when penetration is involved (Hunter and Becker, 1994, Marshall et al, 1991). In general, the sexual arousal patterns of sexually abusive youth appear more changeable than those of adult sex offenders, and relate less directly to their patterns of offending behavior (Hunter and Becker, 1994, Hunter et al, 1994). Treatment ResearchWhile funding and ethical issues have made it difficult to conduct carefully controlled treatment outcome studies, a number of encouraging clinical reports on the treatment of sexually abusive youth have been published (Becker and Hunter, 1997). While these studies are not definitive, they provide support for the belief that the majority of sexually abusive youth are amenable to, and can benefit from, treatment. Multisystemic TherapyIn what is perhaps the best controlled study to date, Borduin, Henggeler, Blaske, and Stein compared "Multisystemic Therapy" (MST) with individual therapy in the outpatient treatment of 16 juvenile sex abusers (Borduin et al, 1990). MST is an intensive family- and community-based treatment that addresses the multiple factors of serious antisocial behavior in juvenile abusers. Treatment can involve any combination of the individual, family, and extrafamilial (e.g., peer, school, or neighborhood) factors. MST promotes behavior change in the youth’s natural environment, using the strengths of the youth’s family, peers, school, and neighborhood to facilitate change. In this study, rearrest records were used as a measure of sexual and non-sexual recidivism; the groups were compared at a three-year follow-up interval. Results revealed that youths receiving multisystemic therapy had recidivism rates of 12.5 percent for sex offenses and 25 percent for non-sex offenses, while those receiving individual therapy had recidivism rates of 75 percent for sex offenses and 50 percent for non-sex offenses.

Other Treatment ResearchProgram evaluation data suggests that the sexual recidivism rate for juveniles treated in specialized programs ranges from approximately 7 to 13 percent over follow-up periods of two to five years (Becker, 1990). Furthermore, juveniles appear to respond well to cognitive/behavioral and/or relapse prevention treatment, with recidivism rates of approximately seven percent through follow-up periods of more than five years (Alexander, 1999). Studies suggest that rates of non-sexual recidivism are generally higher (25 to 50 percent) (Becker, 1990, Kahn and Chambers, 1991, Schram et al, 1991). Findings from outcome studies on adult offenders show higher sexual recidivism rates for individuals who fail to successfully complete treatment programs (Marques et al, 1994). In a recently conducted study, Hunter and Figueredo found that as many as

50 percent of youths entering a community-based treatment program were

expelled during the first year of their participation (Hunter and Figueredo,

1999). Those who failed the program had higher overall levels of sexual

maladjustment, as measured on assessment instruments, and were judged to be at

greater long-term risk for sexual recidivism. Policy Development IssuesTrends in Juvenile JusticeThe rise in juvenile perpetrated violence over the past decade has resulted in legislation designed to enhance public safety and raise the level of accountability of juveniles in the criminal justice system (Hunter and Lexier, 1998). Substantive changes have been made in legal statutes or regulatory policy in over 90 percent of the states. These reforms include changes related to:

The number of delinquency cases waived to adult criminal courts increased by 71 percent between 1985 and 1994 (Szymanski, 1998). The age at which a juvenile may be tried as an adult has been lowered in over half of the states. Twenty jurisdictions

have no minimum age restriction for trying a juvenile as an adult for certain serious crimes (Szymanski, 1998). Legislative changes have also made it more likely that once a juvenile is convicted of a crime in the adult courts, he or she will serve at least some minimum sentence (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 1997). Presently, more than half of the states permit public access to juvenile court records with some age and offense restrictions, while eleven states

permit public juvenile hearings with no age or crime restrictions (Szymanski, 1998). Registration and Community Notification LawsThe registration and tracking of individuals convicted of violent sex crimes or crimes against minors began with the passing of the 1994 Jacob Wetterling Act. The Wetterling Act was amended in 1996, with the passage of "Megan’s Law," which requires (as opposed to authorizing) state and local law enforcement agencies to release information that is necessary to protect the public concerning a specific person required to register. The Pam Lychner Sexual Offender Tracking and Identification Act of 1996 created criteria for mandatory lifetime registration of highly-dangerous sex offenders, penalties for failure to register, and a requirement that the FBI create a national sex offender registry to assist law enforcement in tracking sex offenders when they move.

Under federal guidelines, states are not required to register juveniles who are adjudicated delinquent for a sex crime. However, states may require registration for these youth if they wish to do so. Juveniles convicted as adults are required to register under provisions of these guidelines (Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General, 1998). At least 27 states have enacted registration laws for juveniles convicted (or adjudicated) of sex crimes. In some states, juveniles are subjected to the same registration requirements as adult sex offenders. In others, juveniles register until they reach a certain age (e.g., 18 or 21); in some instances, the court may require continued registration as an adult sex offender once a juvenile reaches that age. Promising Approaches to InterventionThe number of programs providing treatment services to juvenile sex abusers more than doubled between 1986 and 1992, and continues to climb. This growth reflects both increased societal concern about rising rates of juvenile sex offenses and the professional belief that early intervention helps to stem the emergence of chronic patterns of sexual offending. The following is a review of issues essential to the development of successful community-based treatment programming for sexually abusive youth. Coordination between the Criminal Justice System and Treatment ProvidersMost treatment specialists believe that successful programming for sexually abusive youth requires a coordinated effort between criminal justice system actors and treatment providers (National Task Force on Juvenile Sexual Offending, 1993). For juveniles to productively participate in treatment programming, they must be willing to address their problems and comply with therapeutic directives. Adjudication and supervision typically prove useful in ensuring client accountability and compliance with treatment, as well as a means to prevent future victimization. Clinical experience has demonstrated that the suspension of the youth’s sentence contingent upon his or her successful completion of a treatment program is a particularly effective motivator. Under collaborative arrangements, the treatment specialist provides ongoing progress reports to the courts. Those youth who fail to comply with program expectations can be brought back before the court for review.

SupervisionTo date, no studies have been conducted that clearly identify which supervision strategies are most effective with these youth. However, research on adult sex offender supervision suggests that model management strategies involve: intensive supervision and sex offense specific treatment; interagency collaboration, multidisciplinary teams, and the specialization of supervision and treatment staff; the use of the polygraph to monitor therapy and compliance with supervision conditions; and program monitoring and evaluation, which ensure prescribed policies and practices are delivered as planned (English et al, 1996). However, there has been little research on the application of adult conditions to juveniles. Too little is yet known about young perpetrators to apply adult standards to them. The Role of Supervision OfficersIn many programs, parole and probation officers play an integral role in assisting treatment providers by addressing critical issues and supervising youths’ activities in the home and community. Parole and probation officers help evaluate the extent to which clients are productively participating in the treatment program and complying with court and therapeutic directives. They provide an additional link between the provider and youths’ families, and often assist therapists in impressing upon families the importance of their involvement in the youths’ rehabilitative programming. In some instances, parole and probation officers participate directly in the delivery of therapeutic services as co-therapists in treatment groups. While there is little consensus among the treatment community about the proper role of supervision officers in the treatment of young sexual abusers, supervision officers should, at a minimum, communicate and collaborate with treatment providers.

Typically, parole and probation officers provide an essential case management function. This includes analysis (sometimes with the help of social services) of the appropriateness of youth receiving in-home treatment and of the need for supplemental community programming, such as community service projects. As case managers, parole/probation officers also facilitate appropriate communications between treatment providers and other community agencies, such as school officials involved in the youths’ overall care. AssessmentCareful screening is critical to the success of community-based programming. Ideally, this assessment reflects the careful consideration of the danger that the perpetrator presents to the community, the severity of psychiatric and psychosexual problems, and the juvenile’s amenability to treatment. The latter issues involve an assessment of the youth’s level of accountability for his or her sex offenses, motivation for change, and receptivity to professional help. Professionals who are experienced working with sexually abusive youth should conduct these evaluations. Programs should not compromise community safety by admitting youths who are more aggressive and violent, those who have psychiatric problems that are beyond the scope of the community-based program, or those who demonstrate little regard for their actions or interest in receiving help. Clinical AssessmentProfessional evaluation of youth and their appropriateness for placement should be conducted post-adjudication and prior to court sentencing. Clinical assessments should be comprehensive and may include careful record review, clinical interviewing, screening for co-occurring psychiatric disorders, and the administration of both specialized psychometric instruments designed to assess sexual attitudes and interests, as well as those related to more global personality adjustment and functioning.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gaining control of behavior.

| Teaching the impulse control and coping skills needed to successfully manage sexual and aggressive impulses.

| Teaching assertiveness skills and conflict resolution skills to manage anger and resolve interpersonal disputes.

| Enhancing social skills to promote greater self-confidence and social competency.

| Programming designed to enhance empathy and promote a greater appreciation for the negative impact of sexual abuse on victims and their families.

| Provisions for relapse prevention. This includes teaching youths to understand the cycle of thoughts, feelings, and events that are antecedent to the sexual acting-out, identify environmental circumstances and thinking patterns that should be avoided because of increased risk of reoffending, and identify and practice coping and self-control skills necessary for successful behavior management.

| Establishing positive self-esteem and pride in one’s cultural heritage.

| Teaching and clarifying values related to respect for self and others, and a commitment to stop interpersonal violence. The most effective programs promote a sense of healthy identity, mutual respect in male-female relationships, and a respect for cultural diversity.

| Providing sex education to give an understanding of healthy sexual behavior and to correct distorted or erroneous beliefs about sexual behavior. |

The planning and implementation of treatment services ideally reflect the collaborative involvement of the youth, family, and all agencies involved in the youth’s care as well as those agencies serving victims of these youth. Often, this is accomplished by forming an advisory board to oversee the operation of the program and serve as a mediator between the program and the community. These boards typically consist of representatives from public institutions serving youths and families, including the local juvenile court, the department of social services, the prosecutor’s office, the public defender’s office, victim advocacy services, and parents of youthful perpetrators. The advisory board helps to ensure that the treatment program is serving the needs of its clients while meeting community safety standards.

Controversial Areas of Practice

The following areas of practice have generated controversy, and therefore pose special ethical and legal risks for practitioners assessing and treating sexually abusive youth (Hunter and Lexier, 1998).

Involuntary Treatment

Treatment of juveniles who sexually offend is usually court ordered or mandatorily provided in correctional settings. Historically, juvenile courts have prescribed mental health care for youths with an emphasis on rehabilitation. In contrast, adult courts have typically ordered involuntary treatment on the grounds that the youth represents an imminent danger to public safety.

Given the shift of juvenile courts to a more adult-like criminal justice model, and the increasing frequency with which juveniles are being adjudicated and tried as adults, the issue of involuntary treatment may need to be reexamined. Judicial decisions are no longer made with a consistent emphasis on rehabilitation rather than punishment as a means of ensuring public safety. However, many sexually abusive youth may not meet the legal criteria for involuntary treatment based upon imminence of danger criteria.

Pre-Adjudication Evaluations

A number of sexually abusive youth are referred for evaluation prior to the initiation or completion of the adjudication process. Often, these referrals are made by the court, or another public agency, in an attempt to determine the most appropriate disposition for alleged sexual abusers.

Pre-adjudication assessments raise a number of ethical and legal issues. Youths facing prosecution are placed in the position of being asked to reveal information that may be used against them in court. Evaluations present another set of problems associated with the validity of available assessment instrumentation to determine innocence or guilt. There is no scientific basis for assuming that any currently available psychometric or psychophysiological measure of personality or sexual interest is valid for that purpose (Murphy and Peters, 1992).

Risk Assessment

The courts frequently give clinicians the responsibility of determining the youth’s risk of recidivism. These assessments are used to make dispositional decisions and, as a result of legislative mandates, have potential relevance in determining which juveniles should be placed on state registries, as well as whether information about certain sexually abusive youth should be released to the public.

Unfortunately, risk assessment, especially risk of violence, remains an inexact science (Borum, 1996, Monahan and Steadman, 1996). Although a number of risk assessment instruments are emerging as promising in the assessment of risk of adult sex offenders, to date none of these have been validated on a juvenile population. At this time, clinicians working with sexually abusive youth rely on experience, existing research on delinquency and pro-social functioning of youth, and retrospective and actuarial information on adults who reoffend in making their evaluations of the risk posed by a youth.

A recent study has presented encouraging findings on an actuarial scale for assessing risk among adolescent sexual abusers (Prentky et al, in press). In this study, the Juvenile Sex Offender Assessment Protocol (J-SOAP) was used to assess risk on 96 youth receiving treatment in an institutional setting. Results from a 12-month follow-up period suggest that the instrument is reliable, internally consistent and appears to possess concurrent and predictive validity. The J-SOAP is currently being used in a variety of locations and continues to be the subject of empirical scrutiny.

Phallometric Assessment

Phallometry is a diagnostic method to assess sexual arousal by measuring blood flow (tumescence) to the penis during the presentation of potentially erotic stimuli in the laboratory. The plethysmograph is a tool commonly used in phallometric assessment. Use of the plethysmograph with juveniles is an issue of some controversy (National Task Force on Juvenile Sexual Offending, 1993). Research suggests that issues of client age and denial compromise the validity of plethysmographic assessment of juveniles. Younger clients appear to produce less reliable patterns of responding, and those who deny their offenses tend to produce suppressed, and therefore non-interpretable, patterns of arousal (Becker et al, 1992, Kaemingk et al, 1995). Most practitioners agree that phallometric assessment should not be used on youth under the age of 14. Phallometric assessments of sexual arousal patterns are most appropriate for older adolescent males who report deviant sexual interest, and/or those juveniles with more extensive histories of sexual offending. Under these circumstances, such assessments may be useful for identifying youths with emergent paraphilic (sexual deviation) disorders as well as helping youth to become more aware of patterns and strengthen non-problematic interests.

Polygraph

The purpose of a polygraph examination is to verify a perpetrator’s completeness regarding offense history and compliance with therapeutic directives and terms of supervision (Edson, 1991, Emerick and Dutton, 1993). The polygraph is used more often with adult offenders than with juveniles. To date, there is little research on the polygraph’s reliability and validity in the evaluation of sexually abusive youth. Research suggests that results potentially can be affected by a number of influences, including the client’s physical and emotional status, the client’s age and intelligence, and the examiner’s level of training and competency (Blasingame, 1998). Most practitioners using the polygraph indicate that the age threshold for use with juveniles is approximately 14 years old.

Polygraph Legislation in Texas

In Texas, law requires use of the polygraph on certain sexually abusive youth. In 1997, legislation was enacted that prescribed release conditions, including counseling and treatment for adolescents convicted of certain sex offenses. Under this law, youth can be required, as a condition of release from the Texas Youth Commission, to attend psychological counseling sessions and to submit to polygraph examinations in order to evaluate treatment progress (Texas Human Resources Code, Title 3, Ch. 61, Sub. A, Sec. 61.0813).

Arousal Conditioning and Psychopharmacologic Therapies

Therapeutic techniques designed to change patterns of sexual arousal remain controversial. Studies examining the effectiveness of techniques such as arousal conditioning and drug therapies are inconsistent (Hunter and Goodwin, 1992). Concerns about the appropriateness of techniques exposing juveniles to physically or emotionally painful stimuli or involving masturbation render arousal conditioning questionable (National Task Force on Juvenile Sexual Offending, 1993). While several reports about the use of drug therapy have appeared over the past few years, little information exists about the safety and effectiveness of these drugs when used on juveniles. In particular, anti-androgens and hormonal agents have typically not been used with individuals under the age of 18 because of their potential suppression of growth, and the other yet unknown long term risk that they may present. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are helpful in reducing the frequency and/or intensity of sexual arousal and thoughts. SSRIs are a class of antidepressant drugs known to cause a decrease in sexual arousal. Further research is examining the effectiveness of such drugs in reducing deviant sexual behavior.

Legal and Clinical Concerns

Subjecting juveniles to stricter penalties for sex offenses poses special legal and clinical concerns. Legal issues can arise in the courtroom when determining if these youth have the capacity to understand their cases, to properly consult their attorneys, or to make sound decisions regarding their defense (Grisso, 1997). Clinical concerns arise when clinicians place demands on their clients to divulge information that may incur additional restrictions or legal sanctions. Proper warning regarding the limits of confidentiality is necessary and may include referral to parents or attorneys prior to encouraging such disclosures. In many jurisdictions, clinicians develop policies with district attorneys to clarify the consequences of new disclosures in the course of treatment (National Task Force on Juvenile Sexual Offending, 1993). Without these precautions, the reporting of such information may interfere with the development of the therapist/client relationship, an essential component of the treatment process, and increase clinician vulnerability to civil suit (Hunter and Lexier, 1998). As with adult offenders, these policies must address harm done to victims identified through new disclosures and ways to offer assistance to these victims.

Areas for Future Research

Continued research is needed in each of the previously described areas. Research on etiology is especially important to the development of prevention programming for high-risk youths. Presently, the National Center for Child Abuse and Neglect is funding two demonstration projects to evaluate treatment outcomes for pre-pubescent children with sexual behavior problems. Studies on effective supervision strategies for sexually abusive youth are clearly needed. Treatment outcome studies that examine both individual and program characteristics associated with positive treatment outcomes are also needed. Research should focus on early identification of youths demonstrating patterns of escalating aggression and violence. The U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention’s currently funded research on the creation of a typology of juvenile sexual offending behavior will help mental health and criminal justice professionals better understand the major subtypes of sexually abusive youth and the most effective intervention strategies for these groups.

Recommendations for Practice

The following suggestions may be used as guidelines for the ethical and effective treatment of juveniles who abuse (Hunter and Lexier, 1998).

Clinical Assessments:

When possible, clinicians should conduct evaluations after adjudication and before sentencing. Clinical assessments should help determine required level of care, identification of treatment goals and objectives, and estimated risk of reoffending. Clinical assessment should not be directed at determination of innocence or guilt.

Clinicians’ Roles:

Clinicians should carefully explain their role, as well as the limits of professional confidentiality, to juvenile clients and their family prior to conducting a clinical interview or administering assessment tests. Furthermore, it is strongly recommended that consent forms, releases, and/or waivers addressing these issues be signed by clients and their families. It is also prudent to review the above issues with clients’ defense attorneys and/or guardian ad litems representing the youths.

Consent Forms:

Clinicians should consider developing additional consent forms to cover the use of more controversial assessment or treatment procedures (e.g. phallometric assessment, aversive conditioning, and "off-label" use of medications). These consent forms should be specific to the procedure and clearly identify any potential risks associated with it. Clients should understand that these procedures are voluntary and that they are free to decline them.

Phallometric and Polygraph Assessments:

Phallometric and polygraph assessments should be administered judiciously. Phallometric assessment is best limited to males 14 years of age or older with extensive histories of sexual offending, and/or those who self-report deviant sexual arousal and interest patterns. This procedure should only be used with the full, informed consent of the youth, their parent(s) or guardian, and preferably the referral agency. Furthermore, it should only be used with those who admit to their offenses and should generally be conducted with auditory stimuli specifically designed for sexually abusive youth.

Risk Assessment:

Clinicians should exercise caution in rendering judgments of risk that individual juveniles represent for further sexual offending. This is especially true when these judgments will figure prominently in legal dispositions. Such assessments should state that they reflect the best available predictive information on these issues, but that empirical support for risk models is tentative at present.

Treatment Plans:

Clinicians should demonstrate sensitivity to developmental issues in assessing juveniles with sexual behavior problems and formulating intervention plans. Treatment plans should be comprehensive, reflecting a holistic understanding of youths, family systems, and sociocultural environment in which they live.

Supervision Strategies:

Sexually abusive youth have always been in the community, and have been increasingly identified and supervised by probation for many years. Only recently has the field moved toward the development of specialized strategies to manage this unique population. To be sure, this is an emerging area and one where much is yet to be learned. However, many of the approaches commonly used with adult sex offenders (e.g., the use of specialized supervision staff, sex offender specific treatment providers, and the polygraph) are being adopted by juvenile supervision agencies around the country. Models of a team approach to sex offender management—teaming supervision agency staff with therapists, school personnel, victim advocates and others to work closely with the offender, his/her family, and victim(s)—are emerging as among the most promising approaches to sex offender supervision.

Conclusion

Adolescents account for a significant percentage of the sexual assaults against children and women in our society. The onset of sexual behavior problems in juveniles appears to be linked to a number of factors, including child maltreatment and exposure to violence. Emerging research suggests that, as in the case of adult sex offenders, a meaningful distinction can be made between juveniles who target peers or adults and those who offend against children. The former group appears generally to be more antisocial and violent, although considerable variation exists within each population. Although available research does not suggest that the majority of sexually abusive youth are destined to become adult sex offenders, legal and mental health intervention can have significant impacts on deterring further sexual offending. Currently, the most effective intervention consists of a combination of legal sanctions and specialized clinical programming.

Resources

The National Adolescent Perpetration Network, contact: Gail Ryan, M.A., Kempe Children's Center, 1825 Marion Street, Denver, CO 80218, phone (303) 864-5252, fax (303) 864-5179, e-mail: Kempe@KempeCenter.org.

The Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ATSA), Connie Isaac, Executive Director, 10700 S.W. Beaverton-Hillsdale Hwy., Suite 26, Beaverton, OR 97005-3035, phone (503) 643-1023, fax (503) 643-5084, e-mail: atsa@atsa.com.

Jefferson County, Colorado; contact: Leah Wicks, Supervisor, Juvenile Sex Offender Program, First Judicial District Probation Department, 100 Jefferson County Parkway, Suite 2070, Golden, CO 80401.

Acknowledgments

The Center for Sex Offender Management would like to thank Dr. John Hunter for principal authorship of this article. CSOM would also like to thank Gail Ryan and Lloyd Sinclair for their comments and contributions to this document. Edited by Madeline M. Carter and Scott Matson, Center for Sex Offender Management.

Contact

Center for Sex Offender Management

8403 Colesville Road, Suite 720

Silver Spring, MD 20910

Phone: (301) 589-9383

Fax: (301) 589-3505

E-mail: askcsom@csom.org

Established in June 1997, CSOM’s goal is to enhance public safety by preventing further victimization through improving the management of adult and juvenile sex offenders who are in the community. A collaborative effort of the Office of Justice Programs, the National Institute of Corrections, and the State Justice Institute, CSOM is administered by the Center for Effective Public Policy and the American Probation and Parole AssociationThis project was supported by Grant No. 97-WT-VX-K007, awarded by the Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.